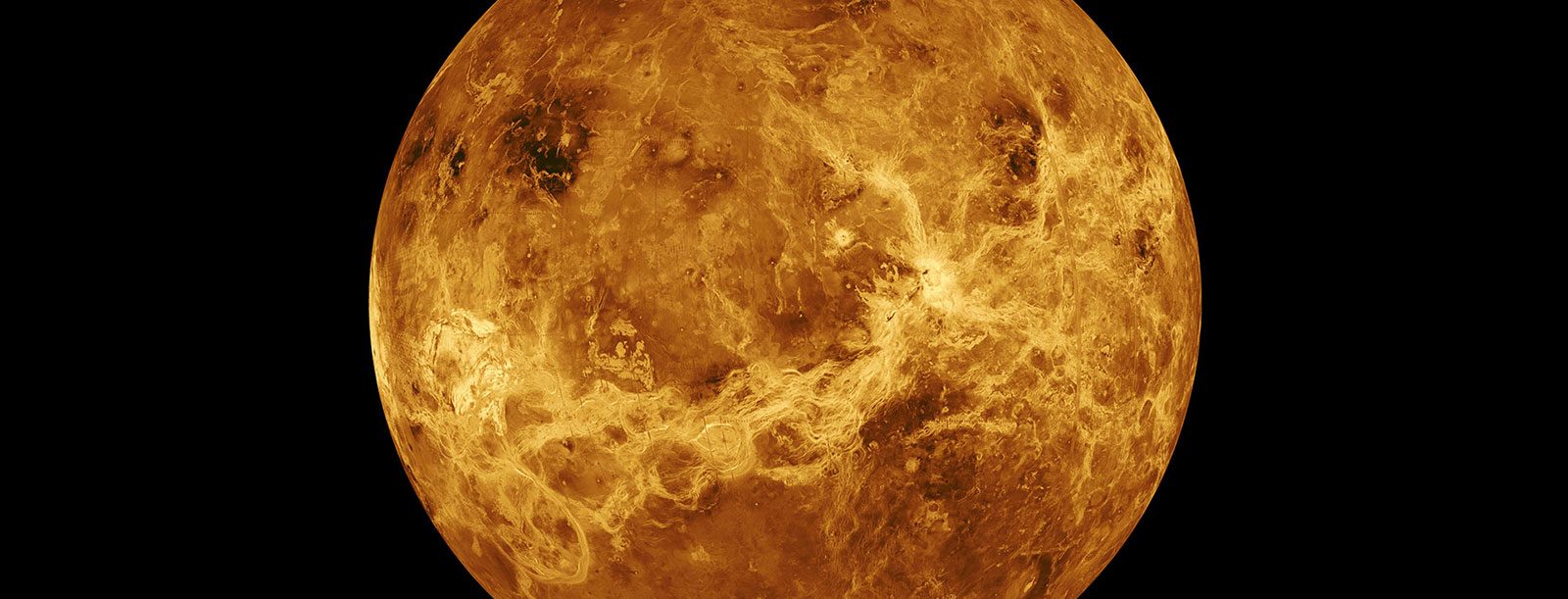

In the earth’s atmosphere, oxygen quickly breaks down all the phosphorous compounds. This does not happen in the Venus atmosphere because it consists almost entirely of carbon dioxide. However, it is very surprising that the phosphorus compound phosphine with the JCMT and ALMA telescopes was found in that atmosphere. The presence of phosphine cannot yet be explained by inanimate chemistry in the atmosphere of Venus, the surface of the planet, lightning in the clouds or reactions under the influence of sunlight. Phosphine could originate from as yet unknown photochemistry or geochemistry, or perhaps from present life. On earth, phosphine is produced by anaerobic bacteria and chemical factories.

The researchers argue that other, unknown ways to form phosphine gas on Venus should be explored. The knowledge network Finding Extraterrestrial Life of the Origins Center is already working on ideas for further research.

“There has been speculation about life in the atmosphere of Venus for decades,” says Daphne Stam (TU Delft). “But before we can say anything with certainty, we need to understand much better where exactly the phosphine is in the atmosphere. Is it in the clouds or above? And perhaps it can be observed that the amount of phosphine fluctuates through the day. Only then it can be stated more clearly whether phosphine on Venus is produced by life. Stam: “We have been doing research on the clouds of Venus in Delft for quite some time.” Daphne Stam is also working internationally on the development of the satellite EnVision, which will, among other things, tell us more about the clouds and the chemistry in the atmosphere and on the surface of Venus. If selected, this satellite could be launched around 2032.

Paul Mason (Utrecht University) adds that research on our own planet teaches us all kinds of things that can be used for research on other planets. “We understand the evolution of our earth better and better. The composition of the atmosphere played an important role in this. With that knowledge, observations of other planets can also be interpreted better and better,” says Mason.

“Phosphorus compounds have been on the radar of Dutch astronomers and astrobiologists for several years now,” says Floris van der Tak (SRON, Groningen). “We try to determine phosphine on comets, in the atmospheres of exoplanets and in interstellar gas clouds, among other things”. The ESA satellite SPICA, which is being developed under the supervision of Dutch researchers, will also be able to measure phosphine in places far away from Earth. If selected, this satellite could be launched around 2032. Dutch researchers affiliated with the Origins Center are also having ideas for missions further in the future to the ice moons Europe and Enceladus. Searching for phosphorus compounds is also high on the list of these missions.

Van der Tak is pleased with the discovery of their British and American colleagues. In addition to the suggestion that there may very well be life in the atmosphere of Venus, this result raises many new research questions. A lot of new research will take place in the Netherlands and abroad in the coming years.

Learn more: Phosphine gas in the cloud decks of Venus (Nature, Sept. 14, 2020)